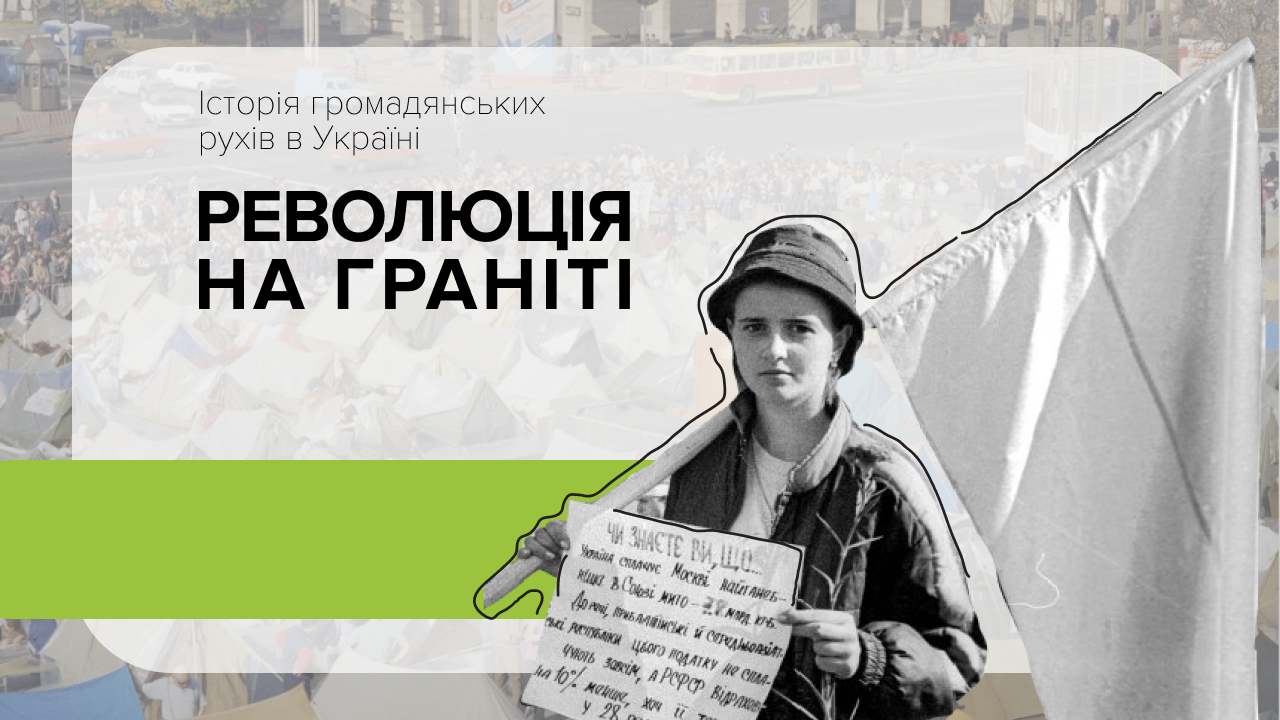

16 days that changed the history of Ukrainian independence: what the Revolution on Granite was like

Civil society is not only about advocating for reforms, volunteering and CSOs. It is also about acts of civil disobedience that directly affect the life of an entire country. In the section "Civil Society Stories", we will tell you about social movements, protests and revolutions that have had a significant impact on the history of our country. Today we are talking about why the Revolution on Granite began, how it lasted and what it achieved.

Background to the protest

The Revolution on Granite began on 2 October 1990 at the initiative of the Ukrainian Student Union and the Student Brotherhood of Lviv Region. The active students were not satisfied with the fact that Ukraine (then the Ukrainian SSR) was being pushed to sign a new union agreement that would make it impossible to gain independence in the future. In addition, they were opposed to Ukrainian youth serving in the military outside the Ukrainian SSR.

The early 1990s was a time of unrest and national movements in the USSR, which was already almost a living corpse. But Ukrainian conscripts could be sent to suppress these movements. No one wanted to fight for the imperialist goals of the Soviet Union, which was falling apart before their eyes, so the students demanded that Ukrainians serve only on the territory of Ukraine. The revolution also demanded the resignation of the government and the head of the Council of Ministers, Vitaliy Masol, to see if the government was ready to make radical concessions. Another demand of the students was the nationalisation of the property of the Communist Party and Komsomol.

The beginning of the revolution

So, 2 October, October Revolution Square (soon to be called Independence Square), dozens of tents and hundreds of inspired students on hunger strike. This was the beginning of the Revolution on Granite.

While the students were setting up on the granite of the square, dozens of police and fire trucks were already concentrated on what is now Instytutska Street. If there was an order, the protest could have been simply washed away and the participants arrested. However, the action did not start near the Verkhovna Rada, as was initially discussed in student circles, but on Maidan, which bought the protesters time. Later, ordinary Kyiv residents joined the students and it became impossible to disperse the action without bloodshed.

The hunger strikers were supported by well-known Ukrainian figures: Lina Kostenko, Maria Burmaka, People's Artist of Ukraine Nila Kryukova, Oles Honchar, and the band "Mertvy Piven" performed for the students.

Over time, the protest began to gain media traction, with picketers taking over buildings of Kyiv universities, trying to break through the police corridor to the Verkhovna Rada, and protest leaders "gobbling up" radio and television airtime. Eventually, the government could no longer ignore the Revolution, so on 17 October, the Verkhovna Rada adopted a resolution that met most of the students' demands. The next day, a celebratory rally was held and the tent city was dismantled.

Of course, the civil disobedience action did not go unnoticed: criminal cases were initiated against some of the participants, and one of the protest organisers, Oles Doniy, was even thrown into the Lukianivka remand centre, but later released under public pressure.

The protest fulfilled its mission and also encouraged people to become active in public life. In particular, many participants in the Revolution later became cultural, political, and public figures in independent Ukraine.

What is important to remember about the Revolution on Granite?

The Revolution on Granite is one of the many protests, uprisings, and wars for Ukraine's independence. Therefore, it is wrong to assume that independence was "given" to us by someone. It was gained by Ukrainians who miraculously self-organised in difficult times and became the driving force of civil society.